“Man is nothing more than what he makes of himself” – Sartre.

The exhibit entrance is hushed.

The Franklin Institute proper has closed for the evening, and the night crowd hasn’t turned out just yet. A maze designed to control long lines is walked by lone visitors who hand their tickets over to a bored-looking worker and turn off their

cell phones at his request.

A ramp goes up to the exhibit space of

Gunther von Hagens’

Body Worlds. Factoids about

the human body – your heart stops when you sneeze – decorate the walls. A turnstile is the final obstacle.

The walls of the room are black, decorated with red cloth hangings, some plain, others featuring quotes –

Kant,

Psalm 8 – or pictures. Spotlights illuminate each specimen. Small fake trees in pots and white rock gardens offer a sense of not-quite-life to contrast with the not-quite-death of the specimens.

A standard, bones-only

skeleton stands by the entrance. It is familiar; similar skeletons reside in biology classrooms around the country.

The gallery is still fairly empty, but the first small crowd is gathered around “

Ligament Body,” a second skeleton. This one is much like the first skeleton, but its bones are connected not with wires but with cartilage,

ligaments, and even some muscles. This skeleton won’t be found in your typical

high school.

“Look at the expression on his face!” a woman remarks at “

The Smoker,” a third skeleton. This one features still more muscles, plus a pair of blackened lungs. The Smoker’s bony fingers clutch a final cigarette. His eyes are wide. He has fingernails.

It is easy to dismiss a bare skeleton as a thing. It may have been a part of a person, once, but it is not a person. The Smoker is a person.

Von Hagens' process, called plastination, replaces or reinforces natural tissue with polymers to prevent disintegration. Some bodies are sliced into slides; other are harvested for individual organs; still more are cut and posed into the statue-like specimens for which von Hagens and

BodyWorlds are famous. There are four official BodyWorlds exhibits on tour, plus various imitators; von Hagens is currently a professor at

New York University, where he is developing an anatomy curriculum for the school of dentistry, where, according to the school’s public relations office, the students enjoy having lifelike specimens without having to dissect

cadavers.

Von Hagens has been surrounded by controversy since he invented the process in the 1970s, as people question the source of the bodies (voluntary donations) and the appropriateness of making entertainment and profit off the dead.

Couples, preteen to mature, embrace as they stare, at first in marvel, then, gradually, for support. A man points out the muscle groups in “

The Basketball Player,” who is playing with an autographed 76ers ball.

“

The Teacher,” his nervous system visible, seems to read from a guide to this very exhibit. A few women decide to learn what he is teaching. They quiz one another in anatomy. Their voices, like the voices of most of the visitors, are hushed. The primary sound is that of the museum’s air conditioning.

Visitors peer into display cases of organs until they approach the “

Blood Vessel Family.” A man, a woman, and a little child perched on the man’s shoulders. Visitors stare, intrigued, at the two adults, whose red, lacy bodies are made up of their plastinated arteries, with no other organs obstructing the view. None can look at the child for more than a few seconds before turning towards one of the adults, or the caption.

This caption explains the process. The bodies’ arteries were filled with plastic, then the bodies were treated over a long period until all but the plastic was dissolved away.

The child offers two thumbs up to the visitor who looks long enough to notice.

Visitors then leave this gallery for the next. The wall hangings here are green.

A literal deathmask rotates in a glass case. The face is covered in gold foil, but the features are distinct. Even so, a caption notes, the process leaves features unidentifiable. The plastination process, then, changes faces but not organs. A man, watching it turn, scratches his nose. Another man points out the face’s dental work, visible from the back.

The face has its original eyelashes.

A smoker’s lung is on display. Two men stare. “You have a cigarette?” one asks the other. Thanks to The Smoker, it is easy to identify each body’s lifetime tobacco habits. Most visible lungs are dark.

A woman gazes into another display case with her companion. “There’s your stomach lining,” she notes. “Well, not

yours.”

Another doorway, and “The Blocking Goalkeeper” stretches out his arms, trying to catch a soccer ball in one hand and his organs in the other. This is the last specimen before the midpoint.

Up a ramp, past the SkyBike, a carefully counterweighted bicycle suspended high above the museum’s lobby. Visitors familiar with the Franklin Institute are greeted with some normalcy, some familiarity. A glance over the ramp’s railing reveals the ticket booth, the gift shop, the snack bar, the line for the

Imax theater.

Off to one side, curtains hide storage. Two of the exhibit’s more famous bodies, “The Swimmer” and “

Rearing Horse with Rider,” are packed away, replaced by more recent creations.

Visitors whip out cell phones or chat among themselves, taking advantage of the excuse to raise their voices. The intermission is welcome; the tension lifts palpably.

At the top of the ramp is the next gallery. The cream and gold walls give the exhibit a classical feel, rather than the ethereal one of previous galleries. Pink and purple banners hang down. Three visitors talk loudly as they approach, but their voices drop immediately.

Lines of viewers, headsets pressed to their ears, listen to the official audiotour, available at $6 a piece. The crowds, which build up as the evening progresses, are at their peak around exhibits that correspond to the tour.

“3D Slice Plastinate” could probably be recognized by his loved ones, were they to see him in the museum. His many tattoos are all visible on his sliced skin; a handful of teenaged girls admire them. They then examine his rear and giggle. The tattoos, and the man’s pubic hair, remind the viewers: this was a person.

Off to one side, cordoned off by black curtains, is a section on fetal development. This is the only section of the exhibit that tells the story of the people behind the specimens.

The pregnant woman shown had been ill, a caption explains at the entrance. She donated her body to the program after becoming pregnant. She died in her eighth month of pregnancy, and her child could not be saved. Mother and fetus were displayed at the main focal point of this secluded room. Her existence was apparently not controversial enough; she is displayed in a classic “cheesecake” pose, propped up on her right arm, her left arm bent behind her head. The fetus is visible in her open womb.

She is surrounded by small display cases on either side, and a row of jars in the middle of the room. The embryos and fetuses shown, the caption assures the visitors, came from historical collections, some dating back more than 80 years. As far as anyone knows, the caption continues, all died in accidents or of natural causes. The unspoken conclusion is that abortion is being kept off the table.

The fetuses are draped in soft black cloth, as if they are resting in blankets. Some are healthy-looking; others have obviously fatal defects. A young man explains the different birth defects to a young woman.

A woman explains pregnancy to a little girl. “How did you know how tiny I was?” the girl asks. She is captivated by the colorless embryos, which she compares to a cheese puff.

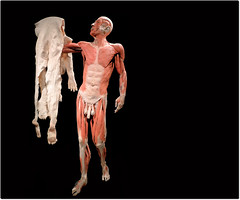

Another doorway, into a room with wooden paneling and floors. A desk is set up with forms so that visitors can send away for information on donating their own bodies. The bodies here span the process, some years old, others brand new. It is easy to see how the plastination process developed. Early specimens were basic, standing or sitting, as in “Winged Man,” who merely stands, his musculature open wide, a white hat perched on his head. Pieces dated 2006 are more complex: a pair of figure skaters are caught mid-dance; a male gymnast hangs from rings as a female gymnast arches over a balance beam. Faces, their skin otherwise removed, have maintained their eyebrows, lips, and the skin around their nostrils. Some visitors compare what they see to pages in their anatomy textbooks.

Visitors do not express any horror, but their bodies betray discomfort. They cross their arms over their chests, or clutch their necklaces. Their hands are clenched or else stuffed into pockets.

Two women make sure the little girl with them is all right. The girl is fine. She only has one concern: “Where’s Pop-pop?”

The good

This is something I wrote for a project and never did anything with. I finally have an excuse. I hope you enjoy it.

As an update: an imitator,

Bodies: The Exhibition, was recently found to have received its specimens from a

suspect source. If you saw this show --

not Body Worlds -- in the US, you may be entitled to a refund.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=1a590f3a-2658-4442-a074-c9c8f92afaf1)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=0dd5e416-79e7-4560-bad2-1ed04b827ba2)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=c44fc4eb-5298-4e15-9396-f5bec910f51b)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=1668be40-2a98-4e7f-9289-355c174ffa26)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=b0490bb2-f19a-4a2e-9eff-4cf4f2cd29dd)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=ca67ed97-f841-4b1c-965e-0398ccd32314)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=58fb3560-0838-442c-82ed-8c55d9fb396a)